The group $SO(3)$

Known as special orthogonal group.

Es el subgrupo de O(3) formado por aquellas cuyo determinante es justo 1. It is the connected component of $O(3)$ which contains the identity element. De entre todas las isometrías, nos estamos quedando con las rotaciones (por definición, una rotación sobre el origen es una transformación que conserva el origen, la distancia euclidiana (por lo que es una isometría) y la orientación). Es homeomorfo al espacio proyectivo de dimensión 3: $P(\mathbb{R}^4)=\mathbb{P}_3(\mathbb{R})$. To see that, think of a full sphere of dimension 3 and of radius $\pi$, in which we identify opposite points in the border. Every rotation in $SO(3)$ can be seen as a vector inside that sphere: the direction indicates the axes and the length indicates the angle (counterclockwise).

Composition of two 3D rotations is a new rotation

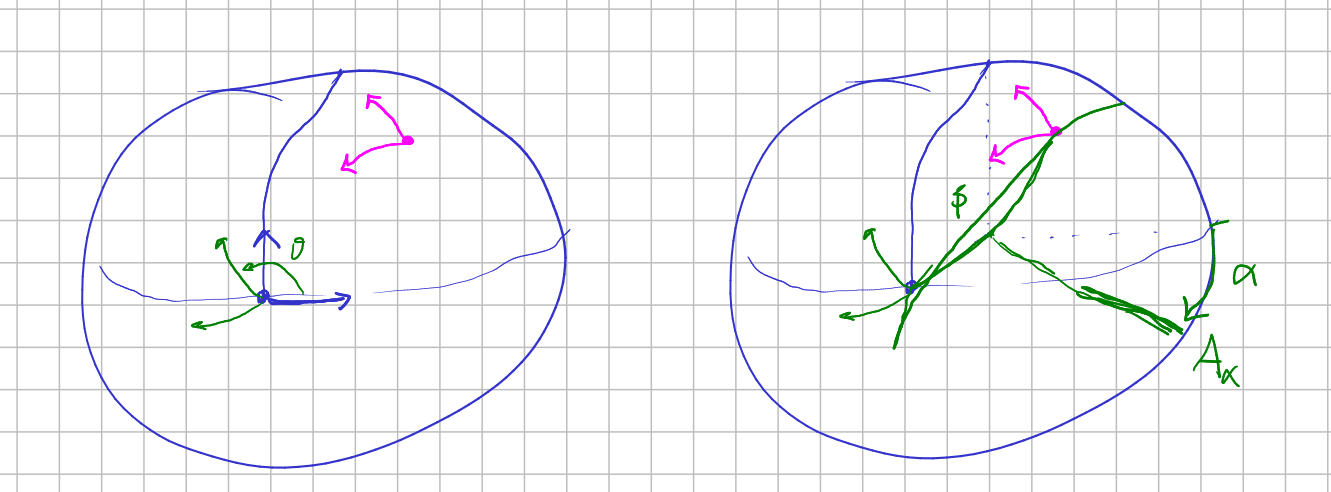

Two ways to visualize it:

- First of all, two reflections give rise to a rotation, the angle being the double of the angle formed by the planes defining the reflections. Reciprocally, a rotation can be seen as the product of two reflection, and we have the freedom to choose one of the reflection, except for the fact that its plane must contain the axis of the rotation.

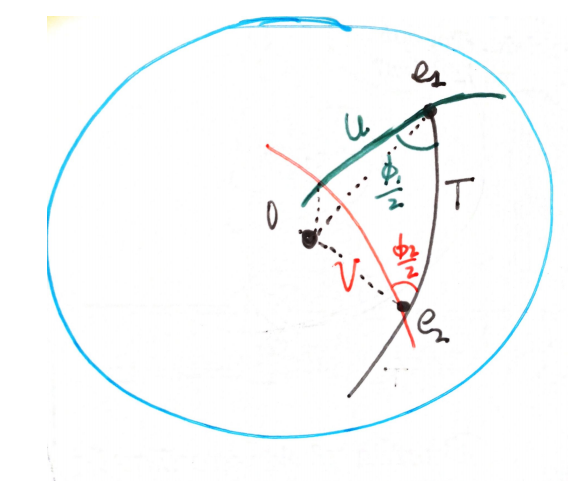

Once you are convinced of this, if you have two rotations in 3D, $R_1=\{e_1,\phi_1\}$ and $R_2=\{e_2,\phi_2\}$, you can fix a reflection along the plane defined by the axis of $e_1$ and $e_2$, call it $T$. So we have that

$$ R_1=TU $$and

$$ R_2=VT $$and therefore

$$ R_2 R_1=VTTU=VU $$is the product of two reflection and hence a rotation.

In the picture, we have expressed reflections by means of the intersection of their defining planes with a unitary sphere.

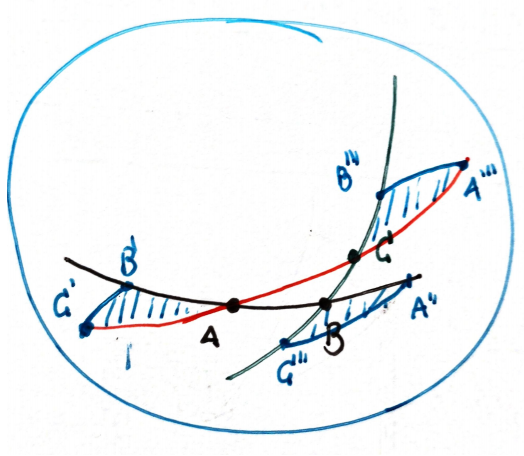

- We can express rotations by giving two points in a unitary sphere. This way, two points $A$ and $B$ determine the rotation $R_{AB}$ whose axis is the orthogonal line to the plane $OAB$ and whose angle is twice the distance from $A$ to $B$ (the arc of the great circle resulting from the intersection of plane $OAB$ with the sphere). Observe that giving a rotation, we have some freedom to choose one of the points. With this convention to define rotations, suppose you have two rotations $R_1$ and $R_2$. We can choose the point $B$ of intersection of the two great circles defined by both rotations in the unitary sphere. Then we have two points $A$ and $C$ such that

and

$$ R_2=R_{BC} $$This way, we get a spherical triangle $ABC$. Now, we are going to construct three more triangles congruent with the original one. We take symmetric point along the great circles and give them names the way you see in the figure:

Triangles $T_1=AB'C'$, $T_2=A''BC''$ and $T_3=A'''B'''C$ are all congruent with $ABC$ since they have in common with it an angle and two sides. But observe that $R_{BC}R_{AB}$ take $T_1$ to $T_3$, the same that it does $R_{AC}$. And since three points determine any symmetry of the sphere, we are done:

$$ R_{BC}R_{AB}=R_{AC} $$More ideas about $SO(3)$

The group $SO(3)$ is simple, it doesn't have any normal proper subgroup (see \cite{stilwell} page 33).

The group $SO(3)$ contains $SO(2)$ in different ways, we only have to mark an axis. So it contains all its finite subgroups. But, moreover, it has three proper finite subgroup: the polyhedral groups.

The set of quaternions of modulus 1 is the 3-sphere $\mathbb{S}^3$, and also has a 2 to 1 homomorphism into $SO(3)$ (see \cite{stilwell} page 14).

What is $SO(3)$ topologically?

First, it can be seen as a filled half sphere in which we identify the shell and the origin. Every interior point (vector) represent an axis of rotation and an angle of rotation (up to $2\pi$). See page \pageref{page:halfsphere} for pictures.

It can be seen, also, like the 3D projective space, $\mathbb{R} \mathbb{P}^3$. We can think of a sphere of radius $\pi$ where we identify the antipodal points.

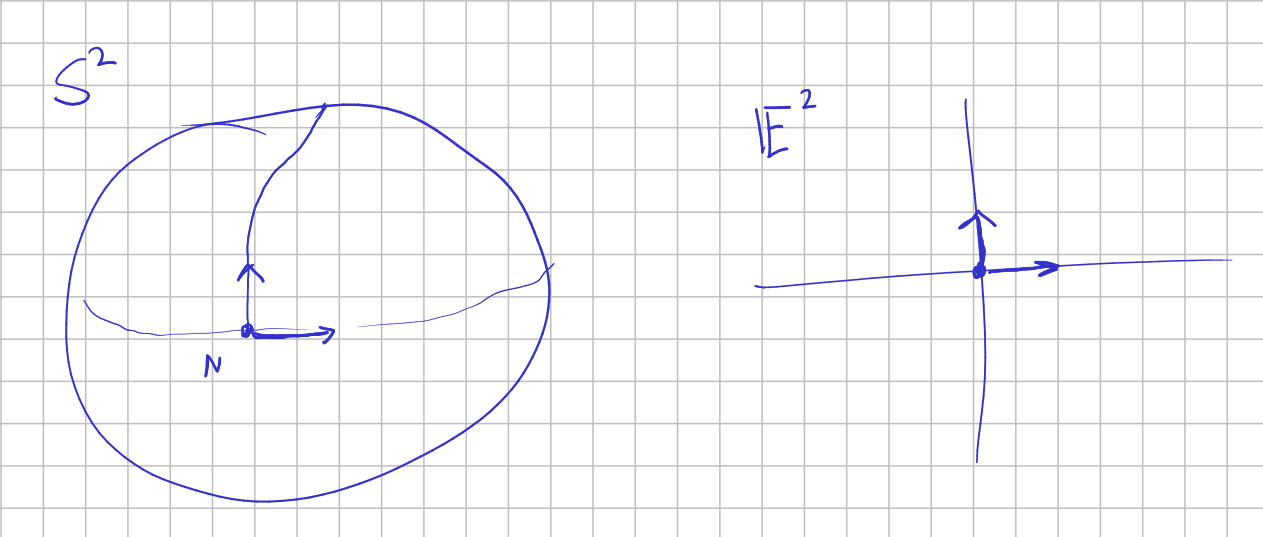

Finally, think of the tangent space to $S^2$, and take only the unitary vectors. This is named $T_0 S^2$ or $S(S^2)$, the sphere bundle of $S^2$. An element of such space is a point $p\in S^2$, which is a unitary vector, and other unitary vector $v \in T_p S^2$, which is orthogonal to $p$. So we can take with the right hand rule a third unitary vector and form an orthonormal basis of $\mathbb{R}^3$, rotated respect the canonical one. This let us watch that $T_0 S^2$ is diffeomorphic to $SO(3)$. See visualization of Lie groups for a explicit construction.

A chart for $SO(3)$. Euler angles

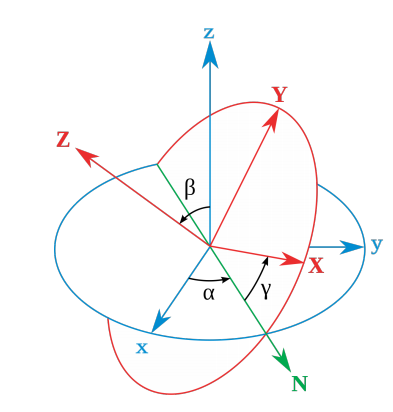

We can specify a general rotation $R$ by mean of 3 angles $\alpha$, $\beta$ and $\gamma$. Fix three axis $x$, $y$ and $z$, and a rotation will be determined by the image of this three axis, $X$, $Y$ and $Z$. If we call $N$ to the intersection of the $xy$ plane with the $XY$ plane, we can carry the first frame to the second one by means of

- A rotation along $z$ of angle $\alpha$, to carry $x$ to $N$. Say $R_z^{\alpha}$.

- A rotation along $N$ (the new $x$) of angle $\beta$, to carry $z$ to $Z$. Call it $R_N^{\beta}$.

- A rotation along $Z$ (the new $z$) of angle $\gamma$, to carry $N$ to $X$. Say $R_Z^{\gamma}$.

This way,

$$ R=R_{Z}^{\gamma}R_N^{\beta}R_{z}^{\alpha} $$This description has never satisfied me, because the axis of rotation are not defined "extrinsically", that is, they are not universal, they do not work for any rotation. They depends on the rotation in particular. But with a little of algebraic manipulation we can recycle these angles to use them with "standard rotations" along the axis $x$, $y$ and $z$.

First, observe that

$$ R_N^{\beta}=R_{z}^{\alpha}R_x^{\beta}R_{z}^{-\alpha} $$since we can express a rotation in a different axis "going and coming back".

Second, by the same reason,

$$ R_{Z}^{\gamma}=(R_N^{\beta}R_{z}^{\alpha}) R_{z}^{\gamma} (R_{z}^{-\alpha}R_N^{-\beta}) $$But then,

$$ R_{Z}^{\gamma}=((R_{z}^{\alpha}R_x^{\beta}R_{z}^{-\alpha})R_{z}^{\alpha}) R_{z}^{\gamma} (R_{z}^{-\alpha}(R_{z}^{\alpha}R_x^{-\beta}R_{z}^{-\alpha}))= $$ $$ =R_{z}^{\alpha}R_x^{\beta} R_{z}^{\gamma}R_x^{-\beta}R_{z}^{-\alpha} $$And therefore our original rotation can be expressed with standard axis

$$ R=(R_{z}^{\alpha}R_x^{\beta} R_{z}^{\gamma}R_x^{-\beta}R_{z}^{-\alpha})(R_{z}^{\alpha}R_x^{\beta}R_{z}^{-\alpha})R_{z}^{\alpha}=R_{z}^{\alpha}R_x^{\beta} R_{z}^{\gamma} $$The embedding in $GL(3)$ is given by

$$ (\alpha,\beta,\gamma) \mapsto\left(\begin{array}{ccc} \cos \alpha \cos \gamma-\cos \beta \sin \alpha \sin \gamma & -\cos \alpha \sin \gamma-\cos \beta \sin \alpha \cos \gamma & \sin \alpha \sin \beta \\ \sin \alpha \cos \gamma+\cos \beta \cos \alpha \sin \gamma & -\sin \alpha \sin \gamma+\cos \beta \cos \alpha \cos \gamma & -\cos \alpha \sin \beta \\ \sin \gamma \sin \beta & \cos \gamma \sin \beta & \cos \beta \end{array}\right) $$with

Another chart: my approach

I guess this have a famous name but I don't know what is.

First, recall that a group can be seen as the set of frames of an associated homogeneous space (see this).

We can look at $\mathbb{S}^2$ with a prescribed frame, in the same way we look at $\mathbb{E}^2$ with the prescribed frame $(O,i,j)$. In this case we fix a point (for example the north pole $N$) and two orthogonal "great circles segments" of unit length.

Any other frame consists of a similar data: another point and two orthogonal great circle segments. We carry the original frame to the latter by means of:

- A rotation on the $z$-axis, of certain magnitud $\theta$

- A choice of an axis $A_{\alpha}$ perpendicular to the $z$-axis with an angle $\alpha$ with the $x$-axis.

- A rotation on the axis $A_{\alpha}$ and certain magnitud $\beta$.

This is totally analogous to $E(2)$, where we perform a rotation $R_{\theta}$ in the origin followed by a translation $\tau_{(a,b)}$. Both $\theta$'s play the same rol, and the pair $(\alpha,\beta)$ determines a kind of translation similar to $\tau_{(a,b)}$.

We could even change $\alpha$ by $-\left(\frac{\pi}{2}-\alpha\right)$, and this way the pair $(\alpha,\beta)$ are similar to polar coordinates $(\alpha,r)$ in the plane $\mathbb{E}^2$.

See maple 071 for the computation of the Maurer-Cartan form with this coordinates.

And what about the Lie algebra $so(3)$?

An element of $so(3)$ can be shown to be an antisymmetric or skew-symmetric matrix, written as

$$ \left[\begin{array}{ccc} {0} & {-c} & {b} \\ {c} & {0} & {-a} \\ {-b} & {a} & {0} \end{array}\right] \leftrightarrow(a, b, c) \in \mathbf{R}^{3} $$and letting

$$ \hat{\mathbf{x}}=\left[\begin{array}{ccc} {0} & {0} & {0} \\ {0} & {0} & {-1} \\ {0} & {1} & {0} \end{array}\right], \quad \hat{\mathbf{y}}=\left[\begin{array}{ccc} {0} & {0} & {1} \\ {0} & {0} & {0} \\ {-1} & {0} & {0} \end{array}\right], \quad \hat{\mathbf{z}}=\left[\begin{array}{ccc} {0} & {-1} & {0} \\ {1} & {0} & {0} \\ {0} & {0} & {0} \end{array}\right] $$we have that the elements of $so(3)$ are of the form

$$ a \hat{\mathbf{x}}+b \hat{\mathbf{y}}+c \hat{\mathbf{z}} $$where $\hat{\mathbf{x}}, \hat{\mathbf{y}}, \hat{\mathbf{z}} \in so(3)$ are the infinitesimal generators for rotations along the $x,y, z$ axis, respectively.

It has the same Lie algebra as SU(2). See relation SO(3) and SU(2) for details.

________________________________________

________________________________________

________________________________________

Author of the notes: Antonio J. Pan-Collantes

INDEX: